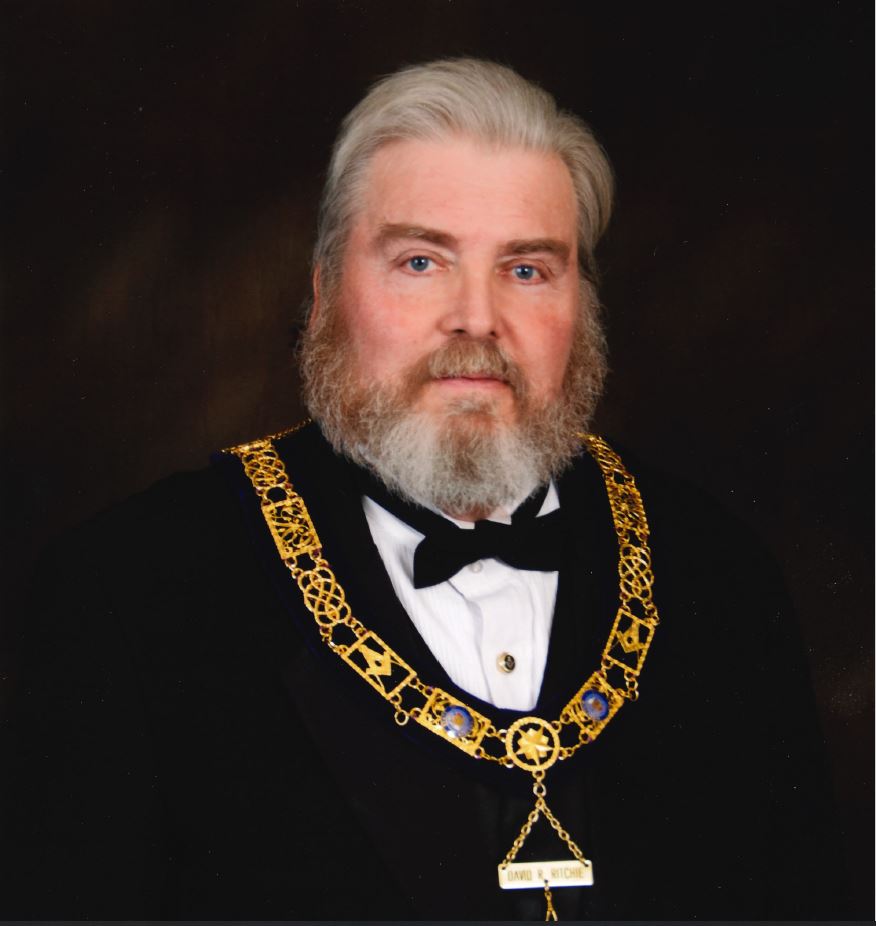

By Brother Richard H. Moen, courtesy of Wisconsin Masonic Journal

Rockdale Beer Cellar was a little-known historical artifact tucked away in a hillside in CamRock County Park in Rockdale in southeastern Dane County. That is, until a certain Freemason saw a clear need for restoration efforts to prevent further damage by ice, snow, and rain. Unused for 140 years and fallen into disrepair, the beer cellar now is a popular destination for park users arriving from dozens of miles around.

First, a description of the structure and its setting. Rockdale Beer Cellar is set in a ravine in a steep hillside, about 50 feet off a gravel recreation trail running along a former millpond and Koshkonong Creek between Rockdale and Cambridge.

The beer cellar was built 170 years ago to store beer in cool air 40 feet into the hillside. Constructed of limestone blocks weighing less than 20 pound to more than 220, stacked one by one and forming an arch, the bulk of the sturdy cellar has withstood the lapse of time since well before the Civil War.

An entrance tunnel leads to the cellar proper. Its vertical walls measure about 18 to 24 inches thick, its opening five feet wide by seven feet high, and its length is 15 feet into the hillside. The cellar itself is a continuous arch about 15 feet wide at the base and 15 feet high at the top. The remaining ceiling extends into the hillside 20 feet, about half its original length. The rear half of the cellar was blasted with dynamite for safety purposes in the early 1900s.

In the 1850s, construction materials readily available in a broad limestone ridge extending a couple miles east and many miles west. Thousands of years of glacial meltwater had eroded a quarter-mile-wide gap in the ridge, exposing limestone bluffs on both sides of the valley. The builders used horses to drag stones down the hill to the site.

Mortar came from limestone pulverized into powder and burned to alter its chemical composition, then mixed it with sand and water to make a strong cement. Rockdale hills also yield a pure, white, silica sand in great abundance, including a “borrow pit” next to the cellar.

Fortitude, Perseverance, and Love of Labor

A casual visit to the site in May 2020 ago recalled memories of aimless excursions into the “beer cave” many decades ago. The interior was entirely intact, despite blasting in a deep and wide limestone quarry a half-mile away for 30 years.

The entrance arch, however, had suffered the ‘ruthless hand of ignorance’ and neglect since the late 1800s. Rain and snowmelt trickling through the ground eroded mortar between the stones, ice expanded in the gaps, stones tumbled down, and damage was severe. Supporting walls had fallen away, two to three feet back on both sides, but five keystones remained at the top of the entrance arch. Only strong mortar and a few cantilevered stones supported the keystones weighing many hundreds of pounds.

The dire condition of this historical edifice prompted a call to action. A basic plan scoped out several phases for the project to appear feasible to the Operative Mason as well as Dane County Parks.

Despite facing an unknown level of effort, uncertain results, and unclear merit in the eyes of the world — not unlike many of our own ventures into Freemasonry – the project appeared worthy.

With authorization from county park staff, the project commenced in July. With about three tons of fallen limestone blocks excavated from a couple feet of soil built up over 140 years, construction began.

Without original pictures or drawing for reference, a combination of historical methods guided the effort: authentic, or documented, history; archaeology, or excavation and analysis of artifacts; and anthropology, drawing on society and culture, including local oral history. A fourth root of history – mystical history – is left to the imagination, but it may explain how the project appeared to come together with a life of its own.

Work on the project continued until rain, snow, and cold forced a halt in mid December. In Spring 2021, the project commenced again and ran through November. A second excavation in 2022 yielded another 6,000 pounds of stones, and work on the sidewalls continued until late November. Along the way, another six or eight tons of stones from a nearly outcrop replaced fallen stones that no doubt had found their way into Rockdale for higher purposes, apparently. In 2023, snow and rain in early spring, followed by high temperatures, delayed the project start. The final stone was set on July 4th.

To grasp the scope of the challenge, imagine a giant, three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Each stone was scrubbed on all sides with a wire brush, and each one ‘fitted with such exact nicety that it had more the appearance of the handiwork’ of someone who thought he knew what he was doing.

Many hundreds of volunteer hours later, mostly solo work, the Rockdale Beer Cellar is preserved to prevent further deterioration for a long foreseeable future. Keystones carefully selected for function and form support the entrance arch. Sidewalls three to six feet high and 30 feet long were discovered, repaired or rebuilt, and extended another 15 feet on each side. The approach area is expanded from a narrow raven to its original 15 feet wide by 50 feet long.

The approach is graveled and graded, and a gentle slope allows walking ease for mobility-challenged visitors. Interpretive signage and solar lighting are planned.

Across the graveled CamRock Trail, a terrace on the bank of the former millpond is leveled and planted to grass for a lawn. The adjacent borrow area is converted to a picnic spot. Two donated permanent benches are installed. A stockpile of 60 cubic yards of waste soil now widens the shoulders of the existing CamRock Trail by about five feet. Hops and wildflowers are planted over the top, with more to come this fall and winter.

Tools For Rebuilding the Temple of Freemasonry

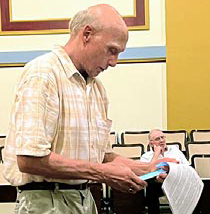

With countless hours of silence and circumspection, the Operative Mason had ample time to reflect on the working tools of Speculative Freemasonry — and to consider how they apply to our work in rebuilding the Craft.

The original “tools addresses” in our ritual clearly arise from a time when our collective moral compass hewed north, more or less. Moral ideals were commonly held in high esteem – not always, not everywhere, and nonetheless prominent in our nation’s history. But the world has changed, and now we face the challenge of rebuilding our virtual Masonic edifice that has suffered ‘the lapse of time and the ruthless hand of ignorance.’ With our shared objective of improving ourselves in Freemasonry, we work with the building blocks at hand, rather than the blocks we must have had many untold generations ago. These contemplations led to a contemporary version of our working tools.

A 24-inch gauge helped to find the right stone to fill a space, thereby ensuring a good fit to be secured with mortar. Most stones needed only a cursory view, even seeming to self-identify, as though they were meant to be chosen. And never mind measuring hours in a day – time seemed to fly by without notice, and work often ended well past sundown, with cleanup continuing into the dark. But we as Free & Accepted Masons may use the 24-inch gauge for the more noble and glorious purpose of measuring ourselves – and a prospective Brother – for fitness in rebuilding our individual temples and our Fraternity. But, like the stones, many prospective Brothers seemed to self-identify, having first been made to a Mason in their hearts.

A common gavel struck off irregularities of some stones retrieved from the rubble, after a chisel scored a line. We as Free & Accepted Masons may use both for fitting ourselves as we rebuild the Fraternity. The chisel carefully marks those parts of our lives that may not meet the high ideals of Freemasonry, and the common gavel of the speculative Mason rids them from our lives.

Compasses devised by this Operative Mason were used to step back and ensure the arc and width of the work were consistent with the original structure. We as Free & Accepted Masons may use compasses – in any form — to ensure that the arc of our moral paths and our Masonic work are consistent with plans laid down in our spiritual, moral, and Masonic trestleboard, so that our zeal for the objective intent of doing good work does not succumb to subjective desires and mere passions for self-satisfying results.

A level set atop a sagging wall ensured fresh stones were set on a level course. A level also set grades for ease of access to the beer cellar. We as Free & Accepted Masons may employ a level-headed gaze at our lives to raise the sags of our former moral stepping-stones and to always meet our Brothers on the level, thereby strengthening the edifice of Freemasonry. And with both feet on the level, a Mason may offer a gentle approach for others seeking the Craft.

A steel brush scrubbed off grime and lichens on stones dug from the rubble so mortar would adhere more firmly. We as Free & Accepted Masons may use a virtual brush for scrubbing our minds and consciences of cynicism, malice, distrust, and other elements of moral decay that may have covered the building blocks of our lives through neglect, or through exposure to common subversive elements all-too-prevalent in today’s society. And thereby preparing our moral building blocks to readily accept the cement of brotherly love and affection.

A water spray rinsed off dirt and grime loosened by the brush to ensure the mortar would unite the stones into one common mass. As Freemasons, we may rinse our hearts and minds with the spiritual waters of the Supreme Architect’s affection, to ensure strong moral foundations and walls, and to become united into one sacred band of friends and Brothers – all the while extending the same to all humankind.

A whisk broom brushed away dirt and debris in cracks and crevasses in the old stone walls to prepare them for rebuilding. As Freemasons, we may brush from our memories the sting of unkind words, casual slights, and other common disgraces that may distract us from our pursuit of the high ideals of Freemasonry.

Rubble buried under decades of decomposed leaves and eroded soil are stones that were solid but irregular in size or shape and, as such, not deemed useful in rebuilding the walls. So rubble was used as a backing to shore up a well-constructed wall against the pressures of surrounding slopes. We as Freemasons may shore up our spiritual edifice — and our Fraternity — with the support of friends and acquaintances who may not quite fit into the Craft for various reasons. But who nonetheless are essentially necessary as a bulwark against moral erosion and societal pressures that may otherwise, over time, weaken our Masonic edifice.

A plumb used by this Operative Mason, after it stopped swinging to and fro, ensured the walls were perpendicular to level ground. We as Free & Accepted Masons may use the virtual plumb, when our thoughts and actions come to rest, as a tool for circumspection to ensure rectitude of conduct needed to meet the higher thoughts and ideals of Freemasonry.

The trowel is an instrument made use of to spread the mortar that unites the stones of the Beer Cellar into one common mass. We as Freemasons may use the trowel to spread the cement of brotherly love and affection, which unites us into one sacred band of friends and Brothers, among whom no contention should ever exist, but that noble contention, or rather emulation, of who best can work and best agree.

And last, but not least, beer – in moderation — was used by this Operative Mason to relieve the mind and body of the day’s toil, to reflect on a job well done, to celebrate a day well spent, and to look forward to another day. We as Free & Accepted Masons likewise may use libations of choice in our hours of rest and refreshment for the same purposes — to relieve our minds and bodies of mundane toils, to reflect on Masonic work rightly done, to celebrate a day well lived, and to look forward to more.

Today, more than a thousand volunteer hours later, and many tons of stones moved around, the historic Rockdale Beer Cellar now is largely intact – as is our Craft, through time, patience, and perseverance. And vision, fortitude, good fortune, and a love of labor.