By Scott Girard, Cap Times, November 6, 2023

Joan Ziegler was about an hour into a lesson on dyslexia in her college class when it hit her.

“I said, ‘Oh my God, that’s me,’” she recalled. “All these years, I never knew what it was, so that was kind of an eye-opener.”

Dyslexia is a learning disability that creates difficulties with language skills, including reading, writing, spelling and pronunciation. Estimates vary on how widespread dyslexia is, but the International Dyslexia Association suggests as many as 15% to 20% of people “have some symptoms of dyslexia,” including slow reading or writing, poor spelling and writing or mixing up similar words.

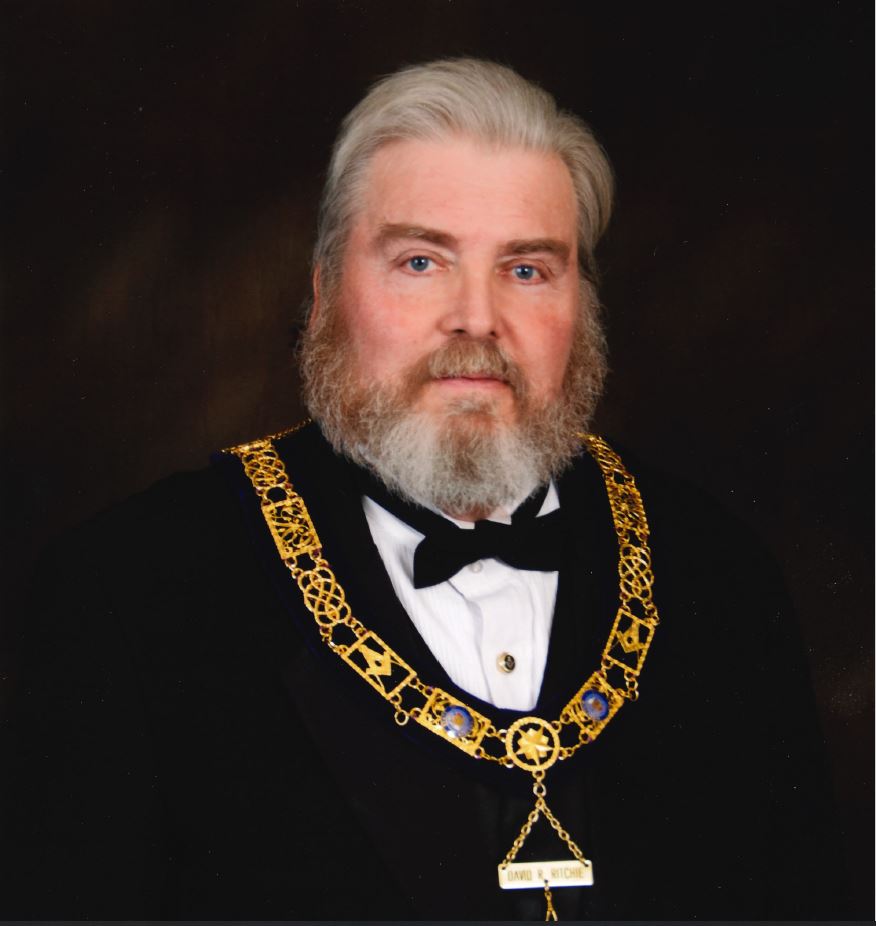

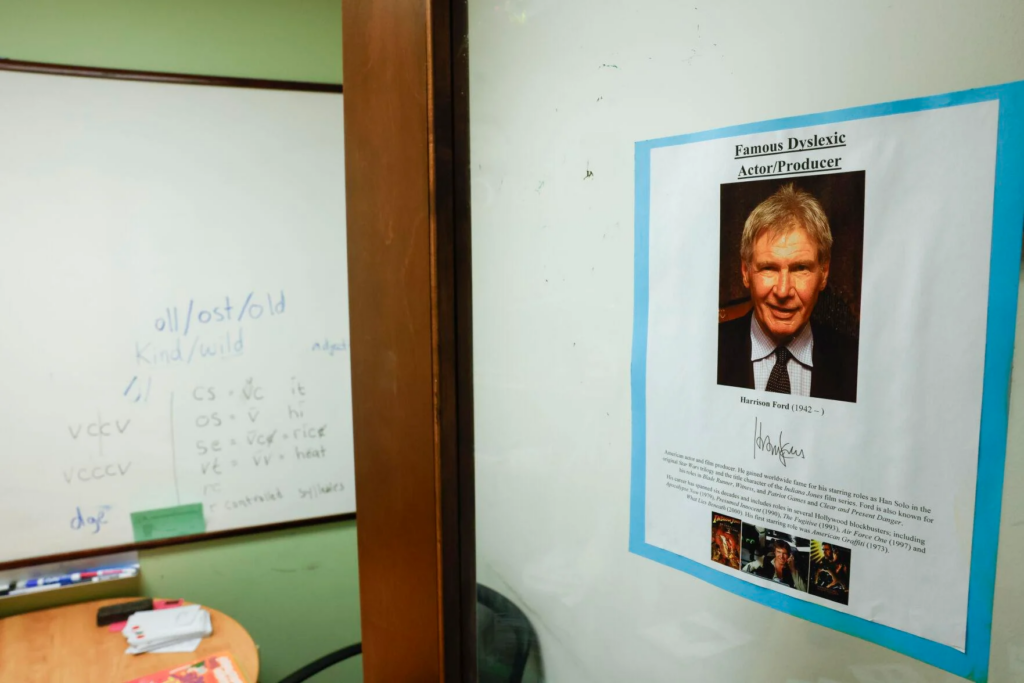

For the last two decades, Ziegler has tutored, and now trains and supervises other tutors at the Madison Children’s Dyslexia Center, helping children who struggle to read like she once did. The center, free to families and located in the Wisconsin Masonic Center, is a charitable organization of the Scottish Rite Masons that aims to help children with dyslexia through tutoring and public awareness.

There’s no shortage of students who could use the center’s services. But having enough people to provide the necessary tutoring is a different story. Becoming a tutor requires 55 hours of classroom instruction, six hours of observing experienced tutors, a 100-hour practicum and a two-year commitment to help at least two students who are on the waitlist.

“The benefit is just having this incredible relationship with this child and teaching them how to read, but it’s a lot of work and not everybody is able to put in that kind of work,” said center director Kelly Kuenzie, who began tutoring there in 2002.

Families on the other side of that wait said it can be “difficult.” Sarah Wilson and her daughter Karina first signed up with the center when she was in fifth grade, and were told it could be as long as three years to get a spot.

This past spring, as she neared the end of middle school, they got in.

“For me, it’s been amazing,” Wilson said. “Everybody there is so nice and Karina’s tutor you can tell is invested in helping Karina become a better reader, and it’s important to her and she cares about Karina’s success.”

Between September 2021 and August 2022, the center had 41 students, 27 graduates and 15 tutors, according to its annual report. It is open Monday through Thursday from 2-8 p.m., with tutoring sessions twice a week for students lasting just under an hour each time. Completing the program takes an average of two years, including a summer session.

Receiving a dyslexia diagnosis and gaining access to a service like the Dyslexia Center requires a neuropsychological evaluation or testing, with an assessment of cognitive ability, reading and spelling.

Megan Beglinger’s daughter was diagnosed in middle school. It didn’t come as a surprise to Beglinger, given she and her husband are dyslexic themselves, but hearing that there was a two to three year wait for the Dyslexia Center made her panic.

“By this time she was already in middle school and school was really hard for her and it was impacting her mental health,” Beglinger said.

It ended up taking less than a year before they got her in, and it made a significant difference in her daughter’s life. Beglinger, having herself experienced the challenges that come with dyslexia, is hoping to pay it forward by becoming a tutor herself.

“Being able to go through there and look back on that negative experience and help to try to turn it around and make it a positive experience is what I’m trying to do,” Beglinger said. “I hated school as a kid, and I don’t want any student or any child that I interact with to feel that poorly about school. It shouldn’t be that way for you.”

An ‘invaluable’ resource

Andy Norderhaug saw his eldest daughter go from below grade level at reading to above in two years at the Dyslexia Center.

“That was a phenomenal experience,” he said. “We always knew she was capable of this growth and expression, it was just being able to have a system.”

She eventually graduated from the program and Norderhaug’s youngest daughter is now a student. He called the center “invaluable.”

“It has just given my daughters more hope for a future and a wider range of career options,” Norderhaug said. “While not everybody knows a person who’s dyslexic, we all think in different ways and have unique ways that we view the world — the Dyslexia Center feels the same way about how they work with their students. There’s not just one type of dyslexia, there’s many different aspects and they really individualize the care and build a relationship with the mentor and the mentees.”

Karina Wilson, the high school freshman who began at the center this past spring, had found school “difficult” for years.

“Seeing what the other kids could do and comparing myself, it was hard for me,” she said.

In the months since she began, she’s learned a host of tools and language rules that help her with reading.

“I like it because it helps me feel more confident in my reading and spelling and stuff like that,” Karina said. “I still struggle at it, but it makes me feel better reading out loud and it’s just a great resource.”

Beglinger’s daughter, now 20, saw similar growth, including in her attitude, her mother recalled. Early on, the car rides home after a full day of school and another hour of tutoring after “were very grumpy and she didn’t want to talk about anything.”

“Then all of a sudden, maybe about three months in or so, she started wanting to talk about it, so our car rides home she started sharing with me,” Beglinger said.

Her daughter eventually shared a specific lesson about how to understand when to use a “c” versus a “k,” a lesson that Beglinger as a teacher was able to share with her own students.

“She was able to use that information to teach me, which was just a wonderful thing to hear and see,” she said. “Just because she was willing to share that information, but also that she was confident enough to tell me what she knows about this.”

‘Nothing more rewarding’

When Kuenzie began as a tutor in 2002, she realized her assumptions about the relationship between intelligence and reading needed revisiting.

“When I started doing the training, it was an eye-opener,” Kuenzie said. “Everything I thought I knew was not true about reading and how people think and how education interacts with people’s intelligence.”

She took over as the center’s director in 2014. The need for tutors is significant, she said, and while the time commitment can be a challenge, there is no cost as long as the tutor takes on two students for a two-year period.

“It’s like a graduate-level course,” she said. “It’s in-depth, but all the information is necessary to know how to best respond to the student because we get the most severe students and a whole variety, so they need to be able to respond appropriately to their individual needs.”

Anyone interested in becoming a tutor can find information on the center’s website, madison-cdc.org.

Ziegler, the longtime tutor, said that every hour of working with a student can also require an hour or two of preparing lesson plans to be ready for a student. It’s important work, though.

“We’re losing some of the brightest brains in the world because they can’t read,” Ziegler said. “They’re not being taught to read, they think differently, they think outside the box.”

She called it a “night and day” difference when a child finds out how to break the code of letters and learn to read, and said there is “nothing more rewarding than seeing a child learn to read.”

“Kids come in angry or depressed or struggling in so many ways with self esteem and other things, and then all of a sudden they learn to read and it’s like the whole world opens up to them,” she said.

Scott Girard joined the Cap Times in 2019 and covers K-12 education. A Madison native, he graduated from La Follette High School after attending Sennett Middle School and Elvehjem Elementary School during his own K-12 career.